Over the millennia, we humans have evolved a number of instincts, automatic responses to dangerous situations that, in our primitive past, helped us achieve the laudable goals of survival and reproduction. Problem is, these instincts were never infallible (a slight advantage is enough for natural selection to retain them), they don’t work in every situation, and we have altered our environment much too fast for evolution to keep up. In fact, given the nature of many of our modern disaster scenarios, these instincts can be not only entirely useless but inappropriate and counter-productive.

6. Panic

Ever walk through your kitchen in the dark, see movement out of the corner of your eye and leap three feet in the air before you even had time to think?

You likely know that as the “fight or flight” reflex, an automatic response to danger evolved to dodge possible harm coming your way without the slow, tedious process of consciously assessing a threat and deciding which evasive maneuver is most appropriate. Your action is being controlled by the amygdala; no, that’s not an elite organization that secretly rules the world, it’s a part of your brain that gets a quick, low-resolution version of sensory input before your conscious brain does and has the chemical authority to make you move very fast without thought. Only later do you get a chance to logically evaluate the situation and remember that bears do not live in your kitchen.

Panic results when the threat does not abate and the amygdala remains in control, trying to get you to go somewhere safe. Now. If nowhere seems safe, well, that screeching alarm in your head might just stay on, demanding that you move quickly, now, preferably in circles while waving your arms in the air.

And again, it does have the authority to make you do that.

Basically, this guy’s in charge.

Fortunately, when disasters happen to large groups of people (and that is what is referred to by the term “disaster” here, events that effect groups) something else takes place. In catastrophe after catastrophe, people remain reasonably calm and well-behaved; they are polite to and even take care of one another. Hierarchies are maintained. Rarely does the social order actually break down. As Lee Clarke, a sociologist at Rutgers University who has studied disaster behavior extensively wrote, “people die the same way they live, with friends, loved ones, and colleagues, in communities. After five decades of studying scores of disasters such as flood, earthquakes and tornadoes, one of the strongest findings is that people rarely lose control.”

Of course, you wouldn’t know this from watching any Hollywood disaster epic, where the public officials in charge of safety are invariably reluctant to inform the citizenry of whatever danger is getting ready to pounce on them, always fearing the widespread panic it will cause.

“If we tell the public about danger, they’ll completely lose their shit.”

And it’s an unfortunate fact that real public officials watch movies, too.

But in reality, you probably don’t really need to worry about this one. In an emergency, you and your neighbors will behave pretty much as you always do, only better. Only if you are trapped alone or lost will you be likely to panic; without the social influence to regulate your behavior, all bets are off. After all, if no one sees you, it doesn’t really happen, does it?

"If I fall down shrieking and sobbing in the forest, do I make a sound?"

5. Gather Stuff

We are tool-using animals; in the wild, our survival depends on our ability to fashion items needed to perform simple tasks like stabbing, clubbing, shooting and digging graves for which we are denied the natural tools. When we face danger, when we are forced to step out into an unknown world fraught with peril, our instincts tell us that we must equip ourselves.

In a survey of 1,444 survivors of the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center, 40% said they took the time to gather various items before leaving. One woman grabbed her purse first, then walked in circles around her cubicle looking for other items to take with her. “It was like I was in a trance,” she said. “I was just looking for items to take with me.” Those items included a mystery novel she was reading.

This might have made sense in the ancient world, when fleeing a coming disaster might have meant leaving the safety of your village to survive in an unfriendly wilderness; the instinct to inventory your possessions and figure out what you might need out there would make a positive difference.

In today’s world, however, that instinct tends to result in people delaying escape from a downed, burning airplane in order to grab their laptops and toiletry kits.

They might keep you waiting in triage, so bring some work to do. Multi-task!

Our tendency to build confined spaces and set them on fire or blow them up puts more of a premium on quick evacuation over equipping ourselves for an unknown future. That, and our ability to put up a Wal-Mart every eight feet generally means you don’t really need to gather possessions quite so fervently. Just get out. The only thing you need to inventory is your ass.

“Ass? Check! Now let’s get the fuck out of here!”

4. When In Doubt, Trust The Herd

We all know that humans are social animals; this stems in part from the fact that we are not particularly big, strong, fast, or tough, and we don’t have claws, sharp teeth, poisonous stingers, or any of that good stuff to defend ourselves with. We simply aren’t well-equipped to survive alone in a natural environment, to say nothing of reproducing without help. So our instincts tell us: above all, stay with the herd. There is safety in numbers, and you must never give them a reason to shun and possibly abandon you.

In a famous series of experiments in the 1950’s, social psychology pioneer Solomon Asch showed that people are terribly reluctant to upset the apple cart, even when that cart is studded with 50mm guns all pointed in their direction.

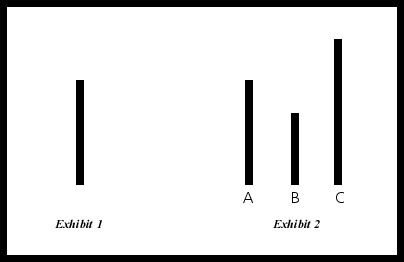

In one study, a roomful of people were shown the following image:

They were then asked which of the three lines on the right matched the length of the line on the left. Obviously, the answer is A.

But here’s the twist: all but one of the people in the room were instructed beforehand to choose B. The real purpose of the study was to see if that lone individual who received no instructions would be swayed by the opinions of others enough to ignore the evidence provided by his own senses and choose B as well. Roughly one-third of the subjects did so.

In another study, a group of people sat in a room and filled out a form. After a few minutes, a vent in the corner of the room began to emit foul-looking smoke. All but one person seated near the vent were instructed beforehand to ignore the smoke, which they knew to be harmless; question was, would that lone individual, who wasn’t in on the secret, stay with the herd and ignore the smoke as well?

Often as not, the answer was yes.

It’s true; even in the face of clear and present danger, we are so afraid of embarrassment, so worried about social stigma, so reluctant to look stupid that we will decide it’s no big deal if the ventilation system has chosen to supply us not with clean air but with something quite possibly lethal.

Meh.

The problem, of course, is that in a real disaster, sometimes everyone takes the same approach; everyone in the room decides not to sound the alarm because no one else is. Freaking out over something that no one else is treating as a problem might cause the herd to abandon you, so it’s best to remain quiet. You don’t want to risk raising a false alarm—what would everyone think?

“Oh, what’s your problem now?”

3. Have a Meeting To Discuss The Situation

According to a study by University of Denver sociologist Thomas Drabek, when told to leave an area in anticipation of a hurricane or flood, a majority of people will check with four or more sources before deciding what to do. These sources may include friends, family, newscasters, or officials. On 9/11, at least 70% of the survivors spoke with others before trying to leave, according to a study by the federal government. They made phone calls, checked TV and internet, e-mailed friends and family. Some took further breaks on their way down, stopping on random floors to call spouses and check CNN.

This is our tribal nature coming to the forefront again, seeking to find a consensus before taking action as a group. As an intelligent species with memories and oral traditions and writing that help us preserve useful information through the generations, we feel a need to consult and tap into those sources in a crisis. For instance, tribal elders may have knowledge and memories of similar situations in the past, and know exactly what needs to be done.

It’s what old people are for.

The problems with this approach should be obvious: it takes time to discuss and come to agreements, and it’s entirely possible the people around you have no relevant prior experience and thus no clue what to do. In a more primitive society, that tribal elder remembers the giant people-eating wave that drowned the countryside after the earth shook and knows that you need to get to high ground now. In today’s world, you put your tribal elder in a rest home, and the guy whose input you’re seeking in a crisis is the same guy who insisted the company absolutely had to install Vista.

“Gentlemen, the room is on fire. I will appoint a committee and we will produce an action memo by the end of the week.”

2. Follow The Leader

As we’ve seen, disasters often cause people to group together against the common threat. And groups, of course, need leaders. Groups that survive are often the ones that someone takes charge of, not by force or bullying but by consensus simply because they are seen to be calm and rational and command respect.

The problems begin when people, responding to the herd instinct, go running off to find a leader, and latch on to and follow one without thinking—and wind up following emergency responders straight back into danger.

There are cases known of people fleeing from fires, running away from danger like any sensible creature would, only to meet an incoming fire truck and actually turn and run alongside it back toward the fire. Jim Cline, a retired New York City Fire Department captain who still trains firemen and emergency personnel, has learned from experience. He now tells his trainees to be wary of this phenomenon. “If something goes wrong, people will tend to follow you,” he says in Amanda Ripley’s The Unthinkable: Who Survives When Disaster Strikes—And Why. “A very strange phenomenon. People will follow you, even when they don’t know why they’re following you.”

Sometimes, it defies explanation.

Obviously, we play follow the leader in these circumstances because we need someone to tell us what to do. Without that, we just might...

1. Freeze Like a Statue

This is perhaps the most common initial response in a crisis. When ominous smoke is filling the fuselage of your plane, when flames engulf the far wall of the ballroom, when the bank robbers pull out the automatic weapons, it’s very probable that you will do...nothing. Maybe stare dumbly straight ahead and blink if you’re feeling particularly energetic.

You, in a crisis.

Why is this a survival instinct? As near as anyone has been able to figure, this phenomenon is similar to the way a mouse goes catatonic while the cat slaps him around playfully before finally getting bored, killing the mouse and leaving him on your pillow as a present. Freezing motionless when threatened is an ingrained response, taking advantage of the instincts that predators evolved to avoid eating rotten or diseased meat. In short, if you don’t move, the critter about to eat you will think you are sick; and if he thinks you’re sick, he loses his appetite and maybe, just maybe, leaves you alone.

Of course, evolution doesn’t like to stand still, so many predators have evolved a response to that behavior. Your cat, for example, has evolved the ability to be fascinated by motionless objects for hours at a time.

Always one step ahead of you.

But the freezing response is so common and occurs so routinely in disasters that people like flight attendants, firemen, policemen and emergency personnel are trained to scream in your face when they need you to move. No gentle suggestion will get through to you in your stupefied state; only the loudest, most urgently expressed commands will get your attention.

It’s like you are a computer and she is trained to punch information into you.

The comment about taking stuff with you reminds me of an anecdote I once read about a flash flood in the U.S. that caught some construction workers off guard. All the Anglos drowned while all the American Indians escaped. When asked why, they said, basically, "When we saw the water coming, the white guys ran for their wallets; we ran for the high ground."

ReplyDelete